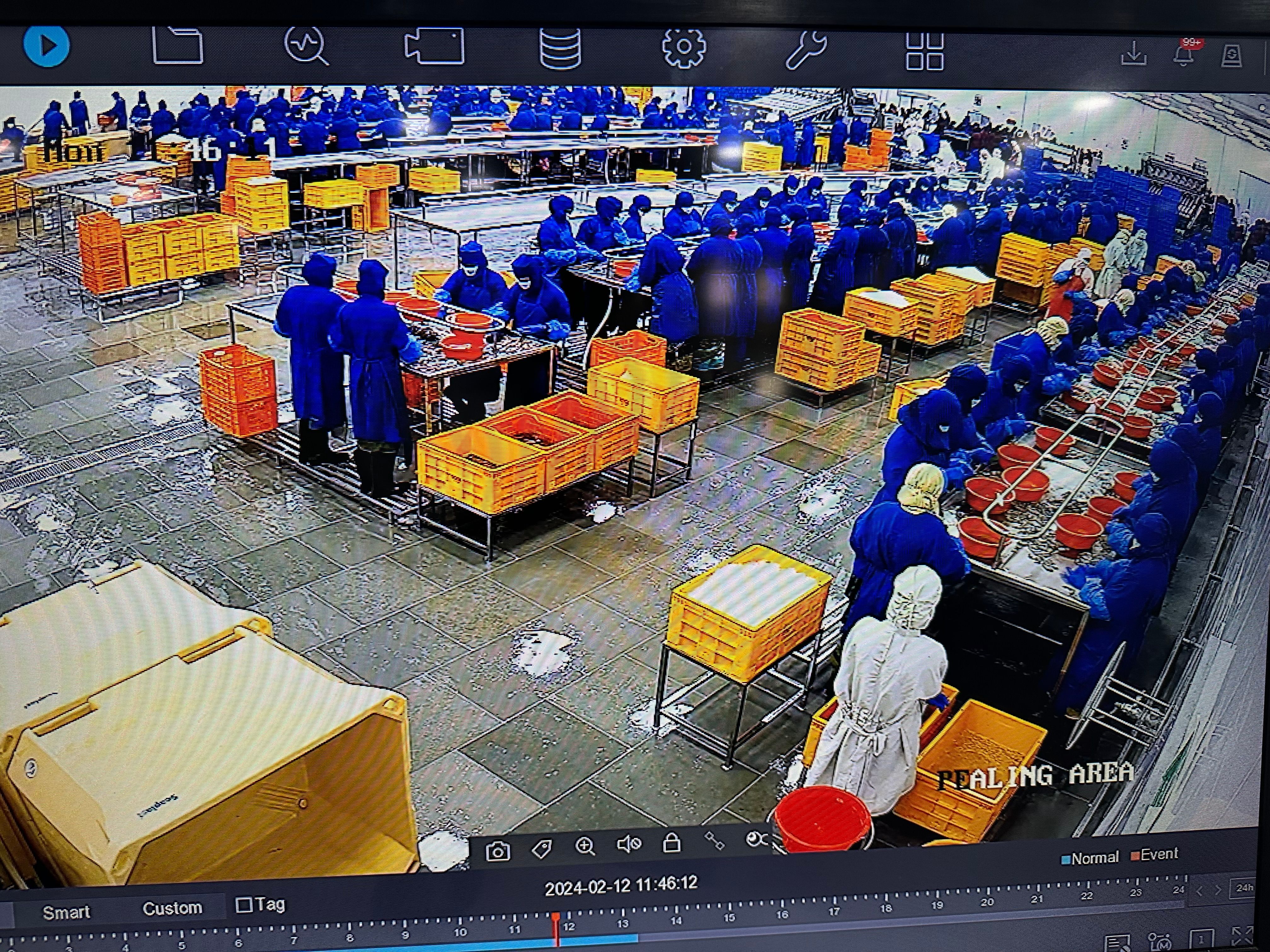

On November 3, 2023, a workplace auditor in India arrived at a shrimp-processing plant in Amalapuram, Andhra Pradesh. They worked for SGS, a Swiss multinational firm that employs nearly 100,000 staff worldwide to provide auditing services. The auditor’s job that day was to conduct an inspection and determine if the plant was in compliance with the requirements set out by Brand Reputation Compliance Global Standards, a non-profit that maintains one of the most relied-upon food safety certification programs in the world. In total, the auditor found only seven minor flaws across the plant’s operations and at the end of the day gave the plant an A grade—the same grade it had received in 2022, certifying it for another year of operation.

The next morning, another SGS auditor arrived at the plant to conduct another inspection. In their report, a more detailed examination produced daily and intended to help Choice Canning stay on top of safety and hygiene issues, printed on official SGS stationery, the auditor cited “filth” and “slime” on processing machines and conveyor belts, flies in the shrimp-packing area, and “fungus” forming on walls. But the auditor didn’t produce this report for public consumption. They produced it for Choice Canning’s management team, who had asked them to identify problems at the Amalapuram facility for their eyes only. “Please keep this very confidential as this is an assignment given to you,” said Jose Thomas, the CEO of Choice Canning, who goes by JT, in one email to SGS. “There are management issues and that is the reason why I have hired your services.”

Dozens of such confidential reports were recently made public by Joshua Farinella, a former manager of the Amalapuram plant. In these reports, SGS auditors detailed problems at the facility, including unsanitary conditions, improper waste disposal, and the presence of mosquitoes and flies near food preparation areas. JT, the CEO of Choice Canning, sometimes became frustrated with his staff in internal emails and WhatsApp messages after receiving SGS’ reports, at one point threatening to dock their pay. Referring to photographs featuring a disorganized cold storage room sent on November 10, 2023, JT said, “Whoever did this will suffer in life!” On occasion, his dissatisfaction appeared to turn to discouragement. “I don't want to be part of this, okay?” he said to one of his managers in a message sent on November 26, 2023. “You deal with this. I'm out of this.” (Choice Canning’s lawyers have since said that the internal audit reports showed how the company went to extra lengths to hold the plant to higher hygienic and food safety standards and the company worked throughout to fix the very problems that were being cited in those reports.)

Choice Canning said that it had been certified under not only the Brand Reputation Compliance Global Standards (BRCGS) but also under another third-party program known as Best Aquaculture Practices (BAP). A spokesperson for SGS, which has conducted BRCGS and BAP audits at the plant, said that it had complied with the food safety audit requirements provided to them and that the audit scope did not cover areas relating to living conditions. SGS also said that “no certification reports are being shared with the client for internal use,” but did not respond to a request for clarification on the reports produced by SGS auditors for Choice Canning’s internal use. Choice Canning said it maintains proper labor conditions at its Amalapuram plant.

Labor and supply-chain researchers say that there are fundamental flaws in the auditing system on which restaurants and retailers around the world depend. One of those flaws, they say, is that the auditing firms often cooperate with the food companies they’re auditing to provide them with certification. The system relies on the producers themselves to hire auditing firms to review their compliance, which gives the auditors a vested interest in the company passing the audit. “Ultimately everybody wants money in the industry,” an auditor who worked for fifteen years in India told the Corporate Accountability Lab, a non-profit that investigates corporate abuse of human rights and the environment. “Nobody is working for the sake of betterment of workers—that is all bullshit.”

That the industry is rife with conflicts of interest, financial and otherwise, between the auditors and those they audit is regularly highlighted by activists, nonprofits and lawmakers—and not just those in the food industry. “While auditors gave examples of the ways in which they had come under pressure by brands and suppliers who were their clients,” Human Rights Watch declared in a 2022 report on the ineffectiveness of social audits, “several auditing experts felt the pressure was higher when suppliers, rather than brands, paid for and appointed auditing firms. Auditors gave examples of how they were asked to delete findings or transmit more serious findings orally or separately in emails, but not in the audit report itself.”

Even some of the auditing firms themselves recognise the flaws in the system. Elevate, a prominent social auditing firm, said in September 2019 that audits were “not designed” to detect issues such as forced labor and harassment. Elevate’s own data lays it bare: in India, over a quarter of of all workers who took the company’s Worker Sentiment Survey said they were victims of sexual harassment, but less than one percent of the social audits conducted by the firm detected any form of inhumane treatment, including sexual harassment.

The result of this breakdown in proper auditing practices is that multiple categories of problematic food products—some produced with forced labor, some containing banned antibiotics, some infected with salmonella or other bacteria—make it to the shelves of supermarkets and on to the menus of restaurants across the U.S.