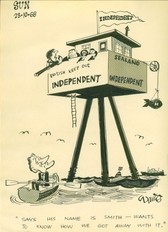

On Christmas Eve of 1966, Paddy Roy Bates, a retired British army major, drove a small boat with an outboard motor seven miles off the coast of England into the North Sea. He had sneaked out of his house in the middle of the night, inspired with a nutty idea for a perfect gift for his wife, Joan.

Using a grappling hook and rope, he clambered onto an abandoned anti-aircraft platform and declared it conquered. He later named it Sealand and deemed it Joan’s.

His gift was no luxury palace. Built in the early 1940s as one of five forts that defended the Thames, the HMF (His Majesty’s Fort) Roughs Tower was a sparse, windswept hulk. “Roughs,” as the abandoned platform was popularly called, was little more than a wide deck about the size of two tennis courts set atop two hollow, concrete towers, 60 feet above the ocean. But Roy claimed his brutalist outpost with the utmost gravity, as seriously as Cortés or Vasco da Gama.

In its wartime heyday, Roughs had been manned by more than a hundred British seamen and armed with anti-aircraft guns, some of whose barrels stretched longer than 15 feet to take better aim at Nazi bombers. When the defeat of the Germans rendered the station obsolete, it was abandoned by the Royal Navy. Unused and neglected, it fell into disrepair, a forlorn monument to British vigilance.

British authorities, not surprisingly, frowned on Roy’s seizure of their platform and ordered him to abandon it. But Roy was as daring as he was stubborn. He had joined the International Brigades at age 15 to fight on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War. When he returned, he signed up with the British army, rising quickly through the ranks to become the youngest major in the force at the time. During World War II, he served in North Africa, the Middle East, and Italy. He once suffered serious wounds after a grenade exploded near his face. In a later incident, he was taken prisoner by Greek fascists after his fighter plane crashed, but he managed to escape. He consumed life with two hands.

Initially, Roy used Roughs for a pirate radio station. The BBC, which had a monopoly over the airwaves at the time, played the Beatles, the Kinks, the Rolling Stones, and other pop bands only in the middle of the night, much to the frustration of young audiences. Defiant entrepreneurs such as Roy answered the call by setting up unlicensed stations on ships and other platforms to play the music 24 hours a day from beyond Britain’s borders. After taking over his platform, Roy stocked it with tins of corned beef, rice pudding, flour, and scotch and lived on it, not returning to land sometimes for several months at a time.

After establishing his new radio station on the gunnery platform and formally giving his wife for her birthday, Roy was out for drinks at a bar with her and some friends. “Now you have your very own island,” Roy said to his wife. As was often the case with Roy, no one could tell whether the gift was sincere or tongue-in-cheek.

“It’s just a shame it doesn’t have a few palm trees, a bit of sunshine, and its own flag,” she replied.

A friend took the banter a step further: Why not make the platform its own country? Everyone laughed and moved on to the next round of pints. Everyone except Roy, that is. A few weeks later, he announced the establishment of the new nation of Sealand. The motto of the country over which he reigned was E Mare, Libertas, or “From the sea, freedom.”

The improbable creation story of the world’s tiniest maritime nation was a thumb in the eye of international law.

Constituted as a principality, Sealand had its own passport, coat of arms, and flag—red and black, with a white diagonal stripe. Its currency was the Sealand dollar, bearing Joan’s image. In more recent years, it has launched a Facebook page, a Twitter account, and a YouTube channel.

Though no country formally recognizes Sealand, its sovereignty has been hard to deny. Half a dozen times, the British government and assorted other groups, backed by mercenaries, have tried and failed to take over the platform by force. In virtually every instance, the Bates family scared them off by firing rifles in their direction, tossing gasoline bombs, dropping cinder blocks onto their boats, or pushing their ladders into the sea. Britain once controlled a vast empire over which the sun never set, but it’s been unable to control a rogue micronation barely bigger than the main ballroom in Buckingham Palace.

The reason goes back to the first principles of sovereignty: A country’s ability to enforce its laws extends only as far as its borders. In May 1968, Roy’s son, Michael, fired a .22-caliber pistol at workers servicing a buoy nearby. Michael claimed that they were mere warning shots to remind these workers of Sealand’s territorial sovereignty. No one was hurt in the incident, but the consequences for Britain’s legal system—and Sealand’s geopolitical status—were far-reaching.

The British government soon brought firearms charges against Michael, for illegal possession and discharge. But the court subsequently ruled that his actions happened outside British territory and jurisdiction, making them unpunishable under British law. Emboldened by the ruling, Roy later told a British official that he could order a murder on Sealand if he so chose, because “I am the person responsible for the law in Sealand.”

In its five decades of existence, no more than half a dozen people, guests of the Bates family, have ever lived on this desolate outpost. On the platform’s flattop, the big guns and helicopters from World War II were replaced by a wind-powered generator, which provided flickering electricity to the space heaters in Sealand’s 10 chilly rooms. Each month, a boat ferried supplies—tea, whiskey, chocolate, and old newspapers—to its residents. In recent years, its permanent citizenry has dwindled to one person: a full-time guard named Michael Barrington.

As absurdist and fanciful as Sealand seemed, the British took it seriously. Recently declassified U.K. documents from the late 1960s reveal that Sealand prompted considerable fretting among officers, who feared that another Cuba was being created, this time on England’s doorstep. These officers debated and ultimately rejected naval plans to bomb the installation. In the decades since its establishment, Sealand has been the site of coups and countercoups, hostage crises, a planned floating casino, a digital haven for organized crime, a prospective base for WikiLeaks, and myriad techno-fantasies, none brought successfully to fruition, many powered by libertarian dreams of an ocean-based nation beyond the reach of government regulation, and by the mythmaking creativity of its founding family. I had to go there.

The sea had summoned me in a dozen ways since I had begun my reporting for the book that would become The Outlaw Ocean, which publishes this week, but Sealand was different from the other frontiers I’d reported on. The audacity of the place was stunning, as were its philosophical underpinnings—an exercise in pure libertarianism awkwardly cinched into the arcane manners of maritime law and diplomacy. I was powerfully drawn to the place

It took me several months and many phone calls to persuade the family to give me permission to visit their principality, but finally, three years ago, I traveled to the platform with Roy Bates’s son, Michael, then 64, and his grandson James, then 29.

The father-son duo picked me up in a skiff in the port town of Harwich shortly before dawn on a frigid windy day in October. The Bates men sat in the middle of the skiff while I sat in the rear as the small craft pounded up and down through the surf. Short and square in build, with a shaved head and a missing front tooth, Michael looked like a retired hockey player. He had a quick laugh and a raucous air. James, on the other hand, was thin and demure. Where James chose his words carefully, his father favored verbal stun grenades: “You can write about us whatever you bloody please!” he said soon after we met. “What do we care?” I suspected he actually cared a lot.

When waves are high, as they were that day, traveling in a 10-foot skiff can feel like riding a galloping horse—but unlike in galloping, the beat shifts often and unpredictably. The hour-long zigzag to Sealand was pure rodeo. My internal organs felt concussed; my legs shook with exhaustion from gripping the oblong seat. In the biting wind, conversation was impossible, so I hung on in silence.

The skiff rocketed across the surf toward a speck on the horizon that grew larger as we approached until I could see the mottled concrete stilts, the wide expanse of the platform above, and the web address painted in bold letters below the helipad in the middle. The famed micronation looked more rugged than regal. As we approached the platform, it became clear that the principality’s best defense was its height. Nearly impregnable from below, it had no mooring post, landing porch, or ladder. We idled our boat near one of the barnacle-coated columns as a crane swung out over the edge, six stories above.

Clad in bright-blue overalls, Michael Barrington, the live-in guard, a graying, round-bellied man in his 60s, lowered a cable with a small wooden seat that looked as if it belonged on a backyard tree swing. I climbed on and was hoisted up—a harrowing ascent in the howling wind. “Welcome,” Barrington yelled above the wind. Swiveling the crane around, he plopped me on deck. The place had a junkyard feel: piles of industrial drums, stacks of plastic crates, balls of tangled wires, mounds of rusty bric-a-brac—all surrounding a whirring wind turbine that seemed ready to pull loose at any minute. As the waves picked up, the whole structure groaned like an old suspension bridge.

Barrington lifted James and Michael, one at a time. Finally, he hoisted the boat itself and left it suspended in the air. “Precautionary,” he said, explaining why he hadn’t left it below in the water.

Michael Bates escorted me from the chaotic deck into the kitchen that served as the Sealandic seat of government. He put on a kettle of tea so we could talk. “Let’s get you through customs,” he deadpanned as he inspected and stamped my passport. I watched his face closely for any sign that it was safe for me to laugh. None came.

I hadn’t quite known what to expect from my visit to Sealand. Before arriving, I had done some reading about the rich and fanciful history of aquatic micronations. At least since Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea was published in 1870, people have dreamed of creating permanent colonies on or under the ocean.

Typically, these projects were inspired by the view that government was a kind of kryptonite that weakened entrepreneurialism. The backers of these micronations—in the first decade of the 21st century, they included quite a few dot-com tycoons—were usually men of means, steeped in Ayn Rand and Thomas Hobbes, and bullish on technology’s potential to solve human problems when unencumbered by government. Conceived as self-sufficient, self-governing, sea-bound communities, these cities were envisioned as part libertarian utopia, part billionaire’s playground. They were often called seasteads, after the homesteads of the American West.

Many tried and failed. In 1968, a wealthy American libertarian named Werner Stiefel attempted to create a floating micronation called Operation Atlantis in international waters near the Bahamas. He bought a large boat and sent it to his would-be territory. It soon sank in a hurricane. In the early 1970s, a Las Vegas real-estate magnate named Michael Oliver sent barges loaded with sand from Australia to a set of shallow reefs near the island of Tonga in the Pacific Ocean, declaring his creation the Republic of Minerva. Planting a flag and some guards there, Oliver declared his micronation free from “taxation, welfare, subsidies, or any form of economic interventionism.” Within months, Tonga sent troops to the site to enforce its sovereignty, expelling the Minervans.

Some of these projects made sense in theory, but didn’t account for the harsh reality of ocean life. At sea, there is plenty of wind, wave, and solar energy to provide power—but building renewable-energy systems that could survive the weather and the corrosive seawater is difficult and costly. Communication options remain limited: Satellite-based connections were prohibitively expensive, as was laying a fiber-optic cable or relying on point-to-point lasers or microwaves that tethered the offshore installation to land. Traveling to and from seasteads was challenging. Waves and storms could be especially disruptive. “Rogue” waves, which occur when smaller waves meet and combine, can be taller than 110 feet—almost twice the height of Sealand.

Moreover, running a country—even a pint-size one—isn’t free. Who would subsidize basic services, the ones usually provided by the tax-funded government that seasteading libertarians sought to escape? Keeping the lights on and protecting against piracy would be expensive.

In 2008, these visionaries united around a nonprofit organization called the Seasteading Institute. Based in San Francisco, the organization was founded by Patri Friedman, a Google software engineer and grandson of Milton Friedman, the Nobel Prize–winning economist best known for his ideas about the limitations of government. The institute’s primary benefactor was Peter Thiel, a billionaire venture capitalist and co-founder of PayPal who donated more than $1.25 million to the organization and related projects.

Thiel also pledged to invest in a start-up venture called Blueseed. Its purpose was to solve a thorny problem affecting many Silicon Valley companies: how to attract engineers and entrepreneurs who lacked American work permits or visas. Blueseed planned to anchor a floating residential barge in international waters off the coast of Northern California. Never getting beyond the drawing-board phase, Blueseed failed to raise the money necessary to sustain itself.

Over the years, threats to Sealand came not just from governments, but from people Roy’s family thought were friends.

In Sealand’s early years, attacks came from fellow pirate-radio DJs. For example, Ronan O’Rahilly, who ran a pirate radio station called Radio Caroline from a nearby ship, tried to storm Sealand in 1967. Roy used gasoline bombs to repel him and several of his men. Later coup attempts on Sealand came from turncoat investors. As we sipped our tea, Michael recounted two examples.

In 1977, Roy was approached by a consortium of German and Dutch lawyers and diamond merchants, who said they wanted to build a casino on the platform. Invited to Austria in 1978 to discuss the proposition, Roy flew to Salzburg, leaving Sealand in the care of Michael, then in his 20s. Upon his arrival in Austria, Roy was greeted warmly by five men who set up a meeting for later that week. When no one showed at the second meeting, Roy grew suspicious and began phoning fishing captains who worked near Sealand, which had no telephone or radio capabilities of its own. When one of these skippers told Roy that he had seen a large helicopter landing at Sealand, he scrambled back to England to discover that a coup had taken place. At around 11 a.m. on August 10, 1978, Michael heard the thwump-thwump of approaching rotors. Grabbing a World War II–vintage pistol from Sealand’s weapons locker, he darted upstairs to find a helicopter hovering overhead, unable to land because of a 35-foot mast intended to deter just such uninvited guests. The helicopter’s bay doors were open, and a man was leaning out, gesturing that he wanted to set down. Michael aggressively waved him off. But within moments, several men had rappelled down a rope dangling from the helicopter and were standing on the platform.

Michael quickly recognized the thick accent and deep voice of one of the men standing before him: It was a voice he had previously overheard on the phone with his father, making plans to meet in Austria. Showing Michael a forged telegram, the men told him that his father had given them permission to come to Sealand as part of their business negotiations. Michael was skeptical, but figured he had no choice but to host the men. So the group headed inside to talk. When Michael turned his back to pour one of them a whiskey, the men slipped out the door, locked him in the room, and tied a cord around the external handle.

Years later, declassified British records and other documents that came to light after the release of the Panama Papers in 2016 made it clear that the puppeteer who had orchestrated the putsch was likely a German diamond dealer named Alexander Gottfried Achenbach, who had approached the Bates family in the early 1970s with the idea of greatly expanding the principality. His plan involved building a casino, a square lined with trees, a duty-free shop, a bank, a post office, a hotel, a restaurant, and apartments, all of which would be adjacent but attached to the Sealand platform. By 1975, Achenbach had been deputized as Sealand’s “foreign minister,” at which point he moved to the platform to help write its constitution. He filed a petition to renounce his German citizenship, demanding he instead be recognized as a citizen of Sealand. Local authorities in Aachen, Germany, where he made the petition, refused his request.

In his effort to win Sealand official recognition, Achenbach sent the constitution to 150 countries, as well as to the United Nations, with the request that it be ratified. But foreign leaders remained skeptical. A court in Cologne ruled that the platform was not part of the Earth’s surface, that it was lacking in community life, and that its minuscule territory did not constitute a living space that was viable over the long term.

Achenbach grew increasingly impatient about his stalled plans for Sealand, and he blamed the Bates family for a lack of commitment. He soon hatched an idea for speeding things along. He hired the helicopter and sent his lawyer, Gernot Pütz, and two other Dutchmen to take control of the platform. The men held Michael hostage for several days before putting him on a fishing boat headed to the Netherlands, where he was released to his parents.

Roy was furious about the coup and decided to take back his micronation by force. After returning to England, he enlisted John Crewdson, a friend and helicopter pilot who had worked on some of the early James Bond movies, to fly an armed team, including Roy and Michael, to the platform. They arrived just before dawn, approaching from downwind to lessen the noise from their rotors. Sliding down a rope from the helicopter, Michael hit the deck hard, jarring and firing the shotgun strapped to his chest, nearly hitting his father. Startled that the intruders were already opening fire, the German guard on deck immediately surrendered. Sealand’s founders were back in charge.

Roy quickly released all the men except Pütz, whom he charged with treason and locked in Sealand’s brig for two months. “The imprisonment of Pütz is in a way an act of piracy, committed on the high sea but still in front of British territory by British citizens,” officials from the German embassy wrote in a plea for help to the British government. In a separate correspondence, a Dutch foreign-affairs officer offered a suggestion for solving the problem: “Is there any chance of a British patrol vessel ‘passing by’ the Fort and somehow knocking it into the sea?” The British government responded that it lacked jurisdiction to take any action.

West Germany eventually sent a diplomat to Sealand to negotiate Pütz’s release, a move that Michael later described as de facto recognition of Sealand’s sovereignty. Made to prepare coffee and wash toilets while he awaited his fate, Pütz was eventually released from Sealand after paying a fine of 75,000 deutsche marks, or about $37,500, to the Bates family.

The incident got shrouded in further confusion a few years later when, in 1980, Roy went to the Netherlands to file charges against one of the Dutchmen—and was represented by Pütz, his former prisoner. This led some observers to question whether the coup was merely an elaborate charade by Roy and Pütz to gain publicity for Sealand and legal recognition of it as a sovereignty. I asked Michael Bates about this allegation.

“There’s photographic proof,” he said, referring to the raid that took back the fortress. “It was entirely real.”

I waited before asking more questions, hoping and expecting he would offer some further explanation for how Pütz went so quickly from foe to friend. He didn’t.

Michael also dismissed my suggestion that the coup was karmic. “No honor among thieves, right?” I asked. Sealand was born not of thievery but of conquest, he rebutted, which felt to me like a distinction without a difference. “We govern Sealand. It’s not a lawless place.” Michael was emphatic on this point, repeating it often.

But the Bates family remain the unofficial historians of Sealand; years of practice have honed their ability to tell a good tale about it.

Michael told me that he had thought Sealand was done with coups after the Achenbach attempt. But in 1997, the FBI called. The bureau wanted to talk about the murder of the fashion designer Gianni Versace on the front steps of his Miami home. “By this point, we were pretty accustomed to getting bizarre phone calls related to Sealand,” Michael said. Versace’s killer, Andrew Cunanan, had committed suicide on a houseboat he had broken into several days after murdering Versace. But during the investigation, the owner of the boat, a man named Torsten Reineck, had presented forged Sealand passports to authorities. Reineck also allegedly drove around Los Angeles in a Mercedes sedan with Sealand “diplomatic plates.”

Michael told the FBI that Sealand had issued only about 300 “official” passports to people he vetted personally. The FBI, in turn, pointed Michael to a website claiming to be run by Sealand’s “government in exile” that sold passports and boasted of a “diaspora” population around the world. Investigators traced the passports and the website to Spain, where they found evidence that Achenbach had waited patiently to stage another coup, though this time from afar. Michael claimed—unpersuasively, it seemed to me—to know nothing about the numerous fraudulent schemes that peddled Sealand’s name and diplomatic credentials online and in the real world.

Still stranger turns were yet to come. Later that same year, the Civil Guard, Spain’s paramilitary police, arrested a flamenco nightclub owner named Francisco Trujillo for selling diluted gasoline at his Madrid filling station. Identifying himself as Sealand’s “consul” to Spain, Trujillo produced a diplomatic passport and claimed immunity from prosecution. Contacted by police, Spain’s Foreign Ministry said no such country existed. The police then raided three Sealand offices in Madrid and a shop that made Sealand license plates. They found that Trujillo had been describing himself as a colonel of Sealand, having even designed military uniforms for himself and other “officers.”

Spanish police also discovered that Sealand’s “government in exile” had sold thousands of Sealand passports embossed with the Bates seal—two crowned sea creatures. These passports had reportedly appeared all over the globe, from eastern Europe to Africa. Nearly 4,000 were sold in Hong Kong when many residents scrambled to obtain foreign documents before Britain handed the colony over to China in 1997. Among the people whom Spanish police tied to the passports were Moroccan hashish smugglers and Russian arms dealers. Several of these underworld characters had also tried to broker a $50 million deal to send 50 tanks, 10 MiG-23 fighter jets, and other combat aircraft, artillery, and armored vehicles from Russia to Sudan, according to Spanish police. The Los Angeles Times reported that about 80 people were accused of committing fraud, falsifying documents, and pretending to be foreign dignitaries.

I asked Michael whether he thought these transactions were part of a larger scheme to take over Sealand. Maybe so, he said. “Most likely, though,” he added, “they just wanted to make money off it as an idea.”

The negotiations for these attempted arms deals were orchestrated by a business called Sealand Trade Development Authority Limited. Recently the Panama Papers included evidence that this company, set up by the Panama City law firm Mossack Fonseca, was tied to a vast global network of money launderers and other criminals.

The story line was loopy, even absurd: Sealand’s German and Spanish “governments in exile” were fictitious duplicates of a questionable original. I found myself thinking of a line from the Jorge Luis Borges short story “Circular Ruins”: “In the dream of the man who was dreaming, the dreamt man awoke.”

Before visiting this strange place, I’d read thousands of pages of old newspaper and magazine articles and declassified British documents. Though most of what Michael told me corresponded to what I already knew from my research, hearing it directly from the source made the stories seem more credible. Or was he just selling me the same malarkey he’d used to get the British government off his back?

I needed some air and asked Michael whether he could give me a tour. We headed out of the kitchen and down the hall and squeezed down a steep spiral staircase. Each of Sealand’s two legs was a tower, stacked with circular rooms. Each room was 22 feet in diameter. Made of concrete, they were cold and clammy and smelled of diesel and mold. Like inverse lighthouses that extended beneath the waves rather than above, most of the floors were under the waterline, which filled them with a faint gurgling sound. Some of the rooms were lit by a single dangling bulb, providing the mood lighting of a survivalist’s bunker. Barrington, Sealand’s guard, joined us on the tour and said that at night, you could hear the pulsing throb of passing ships.

The north tower housed guest rooms, a brig, and a conference room, which was where Barrington stayed. “I like the cold, actually,” he said when I asked whether the space heater was enough to keep him warm in the winter. As we descended, he paused at a room that had been outfitted as a minimalist ecumenical chapel. An open Bible sat on a table decorated with an ornate cloth. A Koran sat on a shelf alongside works of Socrates and Shakespeare. It was a surreal and claustrophobic nook, like a library on a submarine.

We exited the top of the north tower and crossed the platform to the south tower. Michael began telling me about Sealand’s most recent—and in many ways most audacious—plan: to host a server farm with sensitive data beyond the reach of snooping governments. The informational equivalent of a tax haven, the company, called HavenCo, was founded in 2000 and offered web hosting for gambling, pyramid schemes, porn, subpoena-proof emails, and untraceable bank accounts. It turned away clients tied to spam, child porn, and corporate cybersabotage. “We have our limits,” Michael said. (I refrained from asking him why pyramid schemes were okay if spam was not.) He added that in 2010 he had declined a request from representatives of WikiLeaks for a Sealand passport and refuge for the group’s founder, Julian Assange. “They were releasing more than made me comfortable,” Michael said.

The idea of moving online services offshore is not new. Science-fiction writers have dreamed of data havens for years. Perhaps the most famous was in Neal Stephenson’s Cryptonomicon, published in 1999, in which the sultan of Kinakuta, a fictional, small, oil-rich island between the Philippines and Borneo, invites the novel’s protagonists to convert an island into a communications hub free from copyright law and other restrictions.

This science fiction is on the way to becoming real: Since 2008, Google has been working to build offshore data centers that would use seawater to cool the servers—a green way to cut enormous air-conditioning costs. In 2010, a team of researchers from Harvard and MIT published a paper suggesting that if high-speed stock-trading firms hoped to get an edge, they should consider shortening the distance that the information has to travel by relocating their servers at sea. Though these plans have yet to come to fruition, the scholars presented some of their proposals at a conference hosted by the Seasteading Institute.

HavenCo was the brainchild of two tech entrepreneurs, Sean Hastings and Ryan Lackey. Hastings was a programmer who had moved to the British territory of Anguilla in the eastern Caribbean to work on online gambling projects. They had big plans. To deter intruders, they would protect the servers with at least four heavily armed guards. The rooms housing the machines would be filled with a pure nitrogen atmosphere. The nitrogen would be unbreathable, which meant anyone entering the room would have to wear scuba gear. An elite team of coders and online security specialists would police against hackers. To avoid network connections being disrupted by Britain or other governments that wanted to crack down on HavenCo because of the content it hosted, Sealand would have redundant internet connections to multiple countries and, as a further backup, a satellite tie. Customers’ data would be encrypted at all times so that even HavenCo employees would not know what clients were doing.

Most of the plans failed. “It was a disaster,” Michael said mournfully, pausing in a room to stare at a wall of 10-foot-tall empty shelves where HavenCo’s servers were once stacked. Cooling the server rooms became virtually impossible. Most rooms lacked electrical outlets. Fuel for generators was always in short supply. One of the companies that HavenCo was supposed to partner with to get internet services went bankrupt. The satellite link it relied on in its place had only 128 Kbps of bandwidth, the speed of a slow home-modem connection from the early years of the 21st century. The bit about nitrogen being piped into the server rooms for added security was a marketing ploy and never happened. Cyberattacks on HavenCo’s website crippled its connectivity for days. HavenCo attracted about a dozen clients, mostly online gambling sites, but these clients grew increasingly frustrated by HavenCo’s outages and ineptitude, and soon they took their business elsewhere. By 2003, Lackey had grown disgruntled with his partners and left HavenCo.

Michael cited other problems. “Let’s just say that we also didn’t see eye to eye with the computer guys about what sort of clients we were willing to host,” he said. In particular, the royal family nixed Lackey’s plan to host a site that would illegally rebroadcast DVDs. In Lackey’s view, this type of service was exactly the sort that HavenCo had been built to provide. For all their daring, the Bates family was wary of antagonizing the British and upsetting their delicately balanced claim to sovereignty. I couldn’t tell whether the Bateses’ self-preservationist caution toward the British government was the result of maturation or had been there all along, hidden beneath so much bluster. I did have the sense, though, that their falling-out with Lackey had more to do with personality than with principle (“He was just weird,” Michael kept saying) and that their drawing of the line at knockoff DVDs was pure pretext.

As we finished one last cup of tea in the kitchen, Michael grinned. He seemed as proud of the convoluted story behind his family’s bizarre creation as he was of Sealand’s resilience. Taking advantage of a gap in international law, Sealand had grown old while other attempts at seasteads never made it far beyond what-if imaginings. The Bates family was certainly daring, but the secret to Sealand’s survival was its limited aspirations. It had no territorial ambitions; it wasn’t seeking to create a grand caliphate. In the view of its powerful neighbors, Sealand was merely a rusty kingdom, easier to ignore than to eradicate.

The Bates family members are masterly mythologizers, and they eagerly cultivated and protected Sealand’s narrative, which in turn reinforced its sovereignty. Sealand was never a utopian haven; it was always more of an island notion than an island nation, or as one observer once put it, “somewhere between an unincorporated family business and a marionette show.” A Hollywood movie about their project was in the works (it was unclear to me how far along it was, and the Bates family kept hush-hush about details). In the meantime, Sealand is largely financed through the principality’s online “shopping mall,” which is run by the Bates family. The mall’s merchandise is priced not in Sealand dollars, but in British pounds sterling. Mugs go for £9.99, about $14; titles of nobility, £29.99, or $40, and up.

When it was time for me to return to shore, the crane lowered me down in the silly wooden seat to the bobbing skiff below in the North Sea. The goofiness of that childish swing, situated as it was at the entrance and exit of this bizarre place, seemed aptly surreal. Back on the boat alongside Sealand’s concrete legs, I looked up at the rusting platform and waved goodbye to Barrington. He stood above, like some lonely Sancho Panza, keeper of the quixotic vision. The wind raking over us, Michael and James started the engine and turned the boat toward the coast. Sealand slowly receded in the distance as father and son retreated to dry land and their warm homes in Essex, where they proudly reigned over their principality from afar.